While walking along the shores of Lake Zurich, my eyes fell on a poster with a Japanese theme: the Kunsthaus (Museum of Fine Arts) was advertising an exhibition called “Inspiration Japan – Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh.” There was nothing surprising about my noticing this promotion, because ever since I’ve become interested in Japan I act like a magnet for any objects or items related to the Land of the Rising Sun, whether I happen to be in a small town in Hungary or a major city in Europe, and whether my stay is for business or pleasure. However, the moment I pulled out my camera to snap a picture of the poster, a strangely dressed woman pounced in front of the camera gesturing wildly – and acting completely out of place for a country as conservative and formal as Switzerland – telling me at length that I absolutely must go and see the exhibition and promising me a unique and fantastic experience. She also told me the hours when it was most worth visiting the collection, before the crowds coming by bus got there, to have the exhibition more or less to myself. I did as she suggested and went to see what it was about Japanese culture that so inspired the European artists and triggered the enthusiasm of the lady on the street.

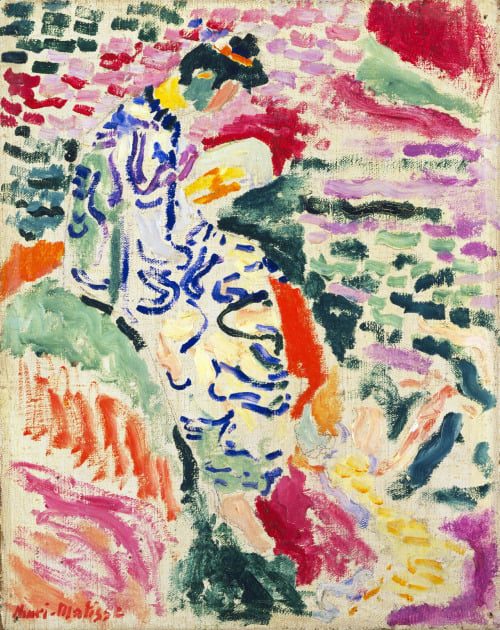

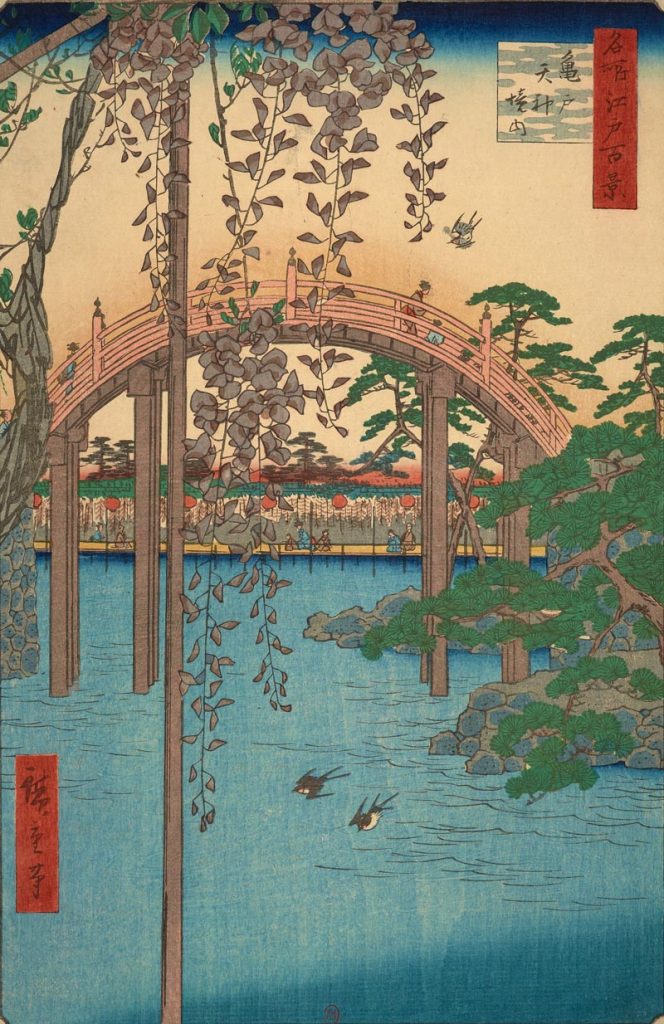

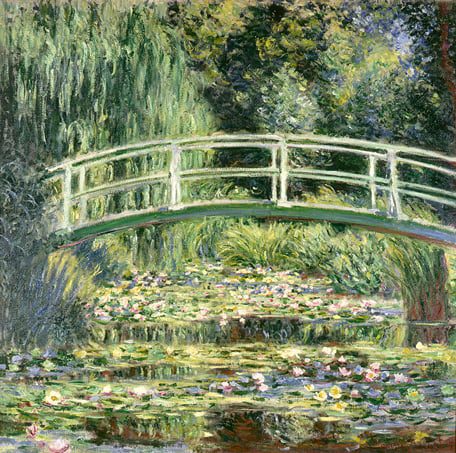

Using the term “Japonisme,” the exhibition covered a timeframe ranging from 1860 to 1910 and presented a collection of Japanese works of art that found their way to Europe over this time, and how they inspired predominantly French artists to work along new lines. The Japanese art included the colored woodblock prints of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) (ukiyo-e) as well as porcelain vases and theatrical masks, along with the masterpieces by the European painters who worked in the latter half of the 19th century, in which I could see a measure of Japanese influence. For instance, Vincent Van Gogh painted a portrait of an acquaintance with a background of Japanese woodblock prints. Another of his paintings is of a geisha with a stern look on her face. Claude Monet painted his own garden at Giverny – which he designed using the Japanese garden as his model. It included a small pond with water lilies and a footbridge going over it. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographs also reflect a Japanese influence in the two-dimensional figures with sharp outlines and typically Japanese color combinations. However, the closest influence can be seen in Pablo Picasso’s erotic drawings, which are modeled on the Japanese shunga (“Spring Pictures”) that offer aesthetic portrayals of everyday sexual pleasure.

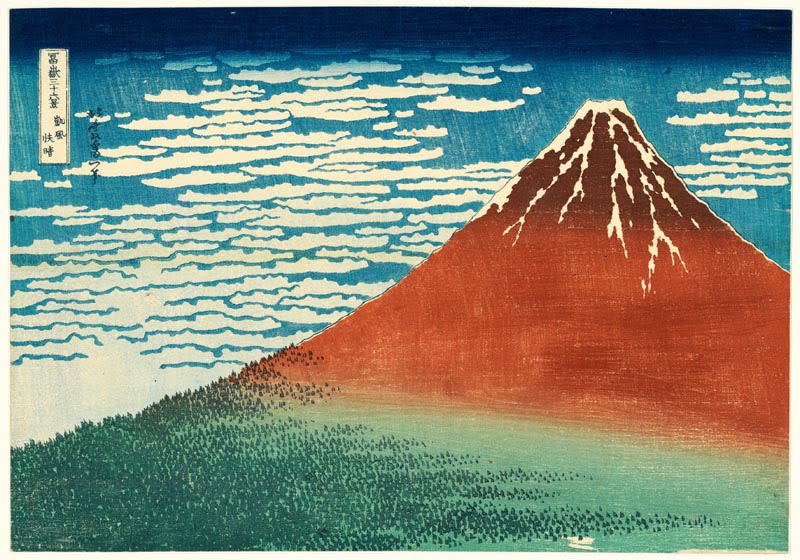

After Japan re-opened its doors to the world in 1854 following over 200 years of isolation, trade between the Japanese isles and Europe began. A series of Japanese works of art – paintings, woodcuts, porcelain – was presented at the 1868 Paris World’s Fair, where the art works took visitors’ breaths away. The well-to-do, and members of artistic circles immediately began adorning their homes with exotic and rare Japanese works of art. Most French painters had their own collection of ukiyo-e woodblock prints that they studied in efforts to unravel the mysteries within them and understand secretive Japan, to which very few people could actually travel, given the huge distance. The Japanese woodblocks presented Europe with new colors and a new perspective. The exceedingly detailed two-dimensional figures were generally presented in scenes from day-to-day life, in a refined and elegant manner using pastel tones. After the colors and compositions of historical figures and battle scenes common to European paintings, the Japanese woodcut must have been quite a surprise, when a horse’s head occupies half an image, while behind it in perspective we see the people walking up and down the street. Another novelty was the precise portrayal of nature, through separate blades of grass or distinct patterns of foam on cresting waves. Still another was how a single theme could be repeated, with each repetition just a bit different. (For instance, Hokusai painted a series of 36 images of Mount Fuji as the seasons changed, showing the mountain from constantly differing perspectives.)

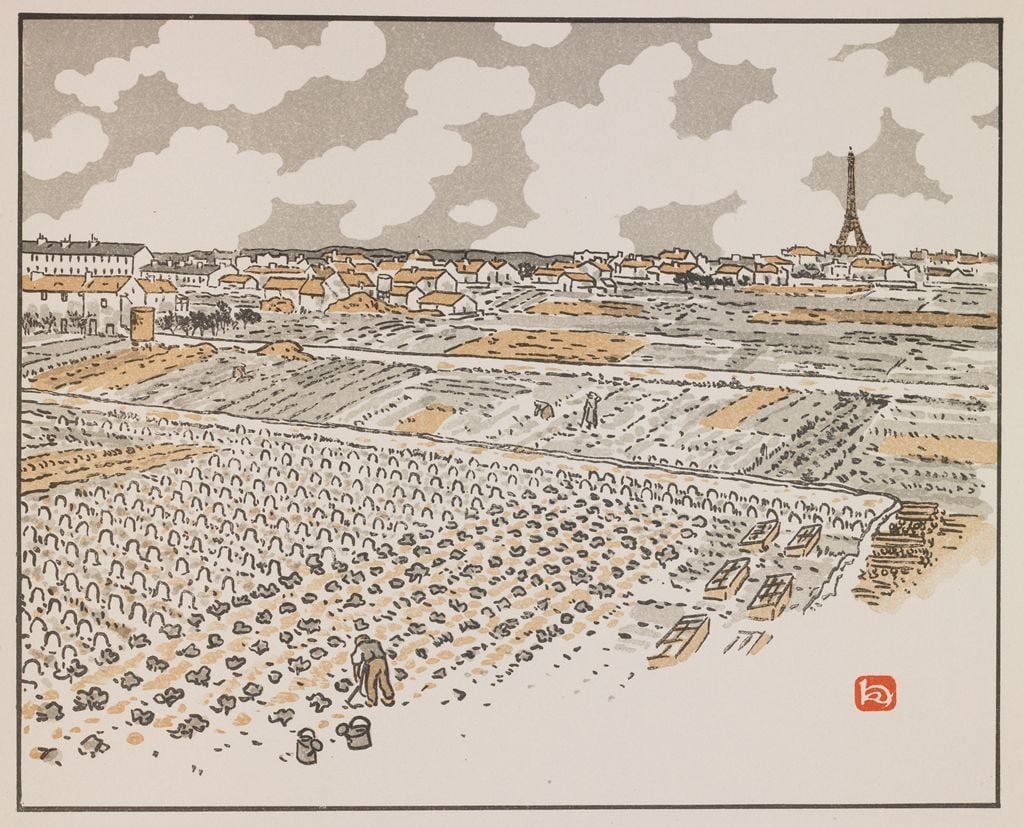

The Kunsthaus exhibition allows the audience to trace the evolution of the Japanese influence: From James Tissot’s and Van Gogh’s Japanese themed paintings I moved on to Henri Riviere’s series, showing the Eiffel tower from 36 angles and Picasso’s shunga-inspired drawings. However, what I saw were not copies of Hokusai, Hiroshige or Kitagava Utamaro (1753-1806) transposed to European art, but the styles unique to the artists themselves – their own ways of seeing their own surroundings – in their own styles. The garden scenes painted by Monet already mentioned reflect his personal approach to light and shade and his way of looking at various weather conditions, portrayed in his images. His attitude to the subject is not Japanese, his figures are distinctly three-dimensional and only the aesthetics of the colors and the perspective, which differs from the conventional style, suggests his Japanese inspiration.