The Japanese Imperial Palace was one of the attractions I was determined to see when visiting Tokyo last year, since I was exceedingly curious about the home of the only monarch in the world still to be called an emperor.

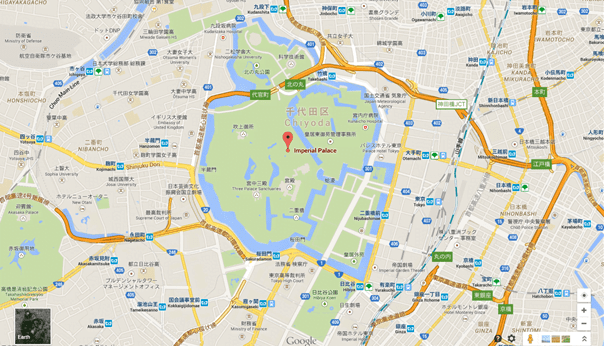

The palace is in the heart of Tokyo in the midst of a huge park, less than 15 minutes walk from the central railroad station. The area is surrounded by a water-filled moat, partly for defense and partly as a safeguard against fire dating from a time when most buildings in the city were made of wood. Today, the palace and its park, located by the Marunouchi commercial district and the skyscrapers and government buildings of the Chiyoda ward, is an island of green. A clearly distinct portion of the huge park, the “East Garden,” may be visited freely but the portion directly connected to the Imperial Palace is only open to tours organized and conducted by the Imperial Household Agency. (I suggest registering weeks in advance!)

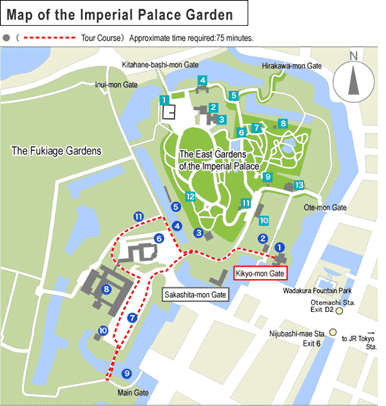

I entered the grounds of the Imperial Palace through the Kikyo-mon gate, together with the other members of the group. There was a briefing and short film presentation at the visitors’ center, followed by a roughly one hour walking tour. Fully 95 percent of the group was Japanese and our guide shared information on the palace and the history of the imperial family in Japanese. Foreign visitors were given audio guides and when stopping at the various points of interest our guide told us the number on the audio guide to press for a brief English summary of the given point. I can still hear the voice going: “englisssshaudioguiiiiideonnumbeeeeerseven,” spoken with military precision.

The site of today’s imperial palace was once Edo Castle, the headquarters of the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868). Edo, meaning “Gate to the Bay”, was the old name of Tokyo. The city was the center of Japanese government administration from the early 17th century onward. With the end of the shogunate in 1868, Emperor Meiji renamed the city Tokyo or “Eastern Capital” and moved into the city. His new residence, located on the site of Edo Castle, was completed in 1888. The exteriors of the wooden buildings reflected traditional Japanese architectural style. It has a huge, gently arched roof structure which almost completely hides the building beneath it. However the roof of the central structure was not covered with wooden shingles but by fireproof copper sheets. The wooden bridges spanning the moat were replaced with ones of stone and iron. In May 1945 most buildings of the palace were destroyed when the city was firebombed by the allied forces. The reconstruction of the central structure and the residences was completed in the 1960s. The two-tiered palace (Kyuden) has retained the traditional forms but is actually a modern building made of reinforced concrete. In front of it stands an abstract “evergreen tree”, which is said to light up at night. The Kyuden is used to receive high-ranking foreign guests and to hold government ceremonies. The average Japanese citizen can approach the palace twice a year – at New Year and on the Emperor’s birthday – when the Emperor Akihito stands on the balcony and greets his people.

According to legend, the Japanese emperor and his family are direct descendents of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. Tradition draws the family tree back to the 7th century BC to the Emperor Jimmu, who allegedly began his rule in 660 BC, although historians have been unable even to confirm his existence. The political power of the emperors gradually weakened, and in 1185 the shoguns (warlords) gained the upper hand and ruled for the next six hundred years. During that time the emperors ruled as the supreme dignities of the Shinto religion, with the power of deities. (They were called Tenno or “Lords of the Heavens” in Japanese.) Emperor Meiji regained political power in 1867. The Second World War and the resulting end to the Japanese Empire was a critical point in the history of the imperial family. When Japan was under American occupation, General MacArthur conducted an investigation to determine whether Emperor Hirohito was responsible for war crimes and deserved to be executed. Finally, MacArthur decided that Hirohito should be acquitted and allowed to retain his throne because, as emperor, he was the symbol of national unity which, MacArthur felt, was necessary for the reconstruction and democratization of Japan. To this end, Hirohito had to renounce the concept of his “divinity” although to this day it is disputed whether he renounced his divinity as an “incarnation of god” or as a “living god.” Some historians believe that MacArthur’s decision prevented Japan from really facing up to its aggressive past and processing it. At any rate, since 1947 the Emperor of Japan is the head of state in a constitutional monarchy with formal responsibilities. Under the Japanese constitution, he is the symbol of the state of Japan and of national unity.

Towards the end of the tour of the palace we passed a section of the moat (Hasuike) full of flowering lotus blossoms and the Fujimi-yagura tower. It was originally built in the mid-17th century but repeated fires and the huge Kanto earthquake of 1923 seriously damaged it. The tower is an early example of the typical uchikomihagi style of construction. The walls are built of natural rocks of different sizes, hammered until the rocks present a smooth exterior surface. I was pleased that the graceful building atop the carefully shaped foundation reflected a bit of the atmosphere of past centuries. That was I imagined the home of the “Lord of the Heavens” to look like.

Sources of the pictures:

The maps: https://www.google.hu/maps; http://www.kunaicho.go.jp

The photos of the monarchs: http://en.wikipedia.org; http://vlaston.webnode.hu

I took the rest of the pictures myself during the visit.