The meetings are, of course, figurative since Enku lived in 18th century Japan, primarily in the Gifu prefecture.

The first time we met was in Moscow, when I was in college. One of my Japanese language teachers, whose name was Komarovsky, mentioned Enku as a favorite of his and showed us a few pictures. In those days I was just taking my first steps in learning about Japanese culture and I was surprised, even shocked, at the modernness. This was particularly true given the environment I was in. It was Moscow in around 1971, when perhaps the worst variation of socialist realism dominated the cultural scene (or at least, the portion the public saw), and modernist leanings as represented by this Japanese artist (deemed “imperialist” or even “clerical”) had no place there. So I was really lucky that the fates had brought me together with an independent-minded teacher.

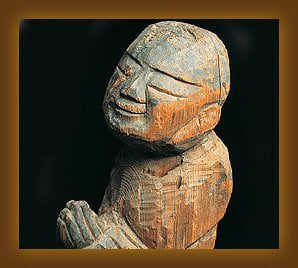

What was it about Enku that grabbed me? Certainly it was the closeness to nature, the warmth radiating from the wood, but most of all it was the broadax or put another way, the crude tool used to shape the images - the simple, at times stone-age or alternatively early 20th century avant-garde abstractions - that radiated his profound humanism, and understanding and love of his fellow-man.

Enku was a simple wandering monk, probably from a peasant family. He was a firm and sincere Buddhist. He carved statues for temples and even for the poorest of the poor. This was his way of attempting to alleviate their pain when they lost family members and to give hope to those who were praying for a bit of luck or happiness. He carved over 100,000 statues, and no two are alike. He did all of his carving with a broadax, and he carved wherever he went – in cities, villages, and in the mountains. Sometimes a tree stump beside a road gave him an idea…

He had no true predecessor as far as his style was concerned, and had no follower either.

Thousand of his works have survived. So, of course, when I got to visit Japan I made a pilgrimage to the region where he had done most of his carving and where the largest number of his works can be found. That region was Hida in the northern portion of the Gifu prefecture, a land of high mountains, huge forests, and in winter, a world of snow.

The “official” art world had difficulty digesting Enku. It was a major event when last year the Tokyo National Museum honored the artist with a major exhibition. For me it was an absolute pleasure to see once again his sometimes monumental and sometimes inch-high but always equally expressive statues. Perhaps the only other places I felt the uncanny intensity of feeling evoked by Enku’s sculpture was at the Hōryū-ji temple (a world heritage site in northern Nara and one of the world’s oldest wooden buildings) and the Ryōan-ji temple (another world heritage site, a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto with a world famous dry landscape garden). Although Enku has even been the subject of a manga (a type of graphic novel), I recommend the real thing. (It may be sufficient to surf the Internet since, luckily, quite a few of his works have been photographed and uploaded.)

I suggest taking your time, and devoting a few minutes to each of the images, perhaps while sipping on a cup of green tea in a quiet room (or at least enjoy some internal quiet while exploring his work), which can bring us closer to him, and him to us...

The source of the first photo:

Copyright Mark Schumacher,

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/busshi-buddha-sculptors-edo-era-japan.html

The other images come from the following websites:

http://photos1.blogger.com;

http://www.tnm.jp;

http://www.ocn.ne.jp;

http://enkumastercarverjapan.blogspot.hu