Lifelong learning is the thing. I recently had dinner in a Tokyo restaurant with the owner and CEO of a Japanese IT firm, where I was asked the dragon toe question. And I have to admit that I hadn’t the faintest idea, even though the dragon is a dominant symbol in Japan (among other places). The dragon is the defender of Buddha and Buddhism and as such it is a near mandatory ceiling decoration for the primary buildings of Buddhist – particularly Zen Buddhist – temples. Below is the dragon that adorns the Tenryu-ji temple (Kyoto), a World Heritage Site. It is some 60 feet in diameter and was painted towards the end of the 19th century (Let me quickly warn you not to draw any far-reaching conclusions on dragon toes from the image because the correct answer is much more complicated.)

However, even before Buddhism was introduced to Japan, the dragon was a part of Japanese legend, and was included among the Shinto gods. Anyway, before going into detail, let me quickly compare the Japanese dragons with ours.

While we Hungarians have a special dragon of our own, Süsü, who has exemplified kindness and generosity to numerous young generations, the European dragon – which includes the dragon in Hungarian folk mythology – represents evil, and must be overcome. This is not the Asian dragon! Although the dragon is considered awe-inspiring and gigantic, it also represents justice, benevolence, and may be a bearer of good luck and wealth. This dragon is also able to shift into a human shape.

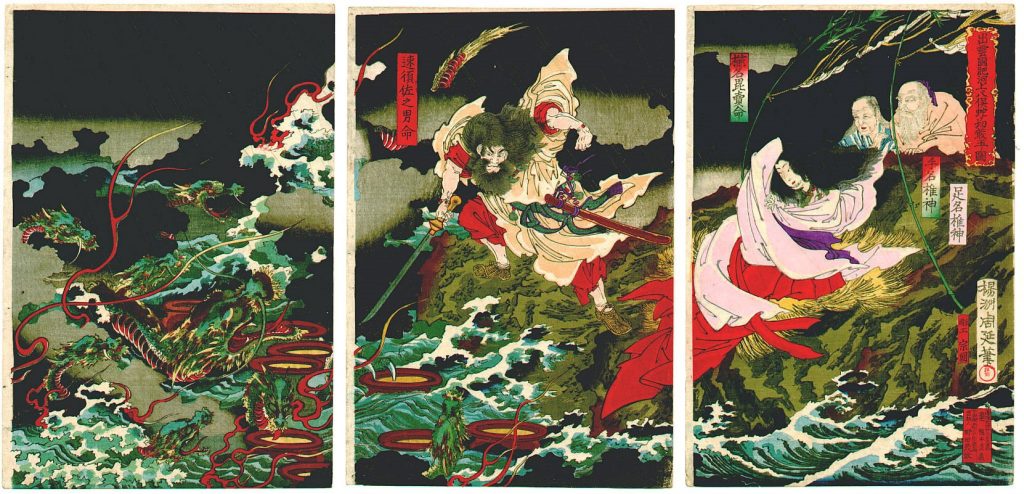

The Japanese dragons typically live in water and are snakelike. And, unlike their European relatives, they do not have wings! However, Japanese dragons can have more than one head. For instance, Susanoo, one of the main characters in Shinto religious mythology, was exiled to Earth after a fight with his sister, Amaterasu-Okami the Sun Goddess, and here he met two Earthling gods. They bitterly told him that each year, they alternately had to sacrifice a daughter to Yamata-no-Orochi, the dragon living in the lake (so we now learn that Japanese dragons can be evil, too), and it was now the turn of the last, the eighth daughter. Susanoo, the hero, is obviously not going to let this happen: with a clever trick he gets the eight-headed eight-tailed dragon drunk and cuts off its heads. However, while cutting off the tails, his sword is dented and thus the miraculous sword, Kusanagi-no Tsurugi, which became a symbol of the power of the Japanese emperor, came out of the tail of the dragon (the other two symbols are the bronze mirror Yata no Kagami and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama, which make up the three items of regalia).

However, the connection between Japan’s imperial family and the dragon goes deeper than this. The legendary first emperor, Jimmu, is said to be a direct descendant of the dragon! Without continuing my list of Japanese gods, whose names we can never manage to learn, I will simply say that Jimmu’s grandmother was the daughter of the God of the Sea, the Dragon King. She gave birth to a son from a human father and then changed into a crocodile and returned to the underwater kingdom.

But, to leave the Shinto legend at that and return to Buddhism, dragons are important to the Buddhist religion. A number of temples, including Ryoan-ji, whose rock garden has made it world famous, have been named after dragons. Ryoan-ji is the Temple of the Tranquil Dragon. There is a popular excursion site, Enoshima, near Kamakura, the ancient capital city just next to Tokyo. A dragon plays the main role in the legend of the island’s origin, so naturally the dragon is the dominant decoration of the temples in the area.

Each year, the Kinryu no mai, meaning the dance of the golden dragon, is held at the Senso-ji Temple, the famous Tokyo temple located at Asakusa. This is one of the major celebrations at the temple.

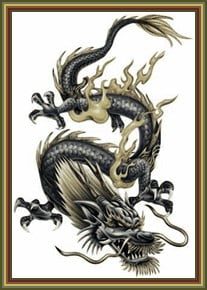

Last but not least, dragons are exceedingly popular among tattoo artists; they are among the top decorations chosen.

I think we can conclude that the Japanese dragon is not a mere import, for there are a number of ancient, original Japanese dragons.

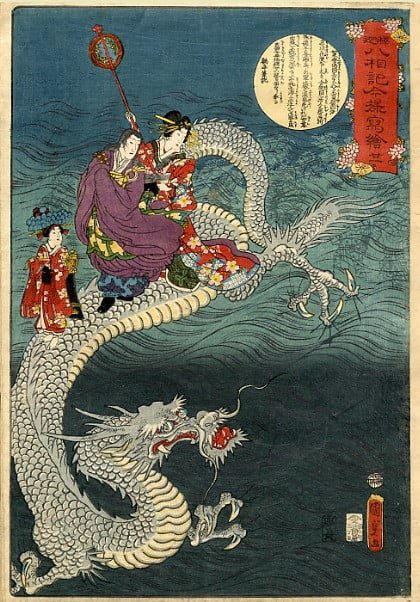

Now, – as often happens in Central Europe, too – this is where the complications begin. Quite a number of significant Asian nations lay claim to the dragon as their own original product, China and Korea among the most important of them. As such, the Japanese had to create a unique “national dragon” to keep the “dragonology” distinct. The following image is of a Japanese dragon as portrayed by Utagawa Kunisada II, with Buddha traveling on the back of the dragon.

In contrast with the first illustration, it is eminently clear here that the true Japanese dragon has three toes! The Korean dragon has four and, according to the Koreans, this clearly demonstrates the superiority of their dragon to the Japanese variety, which only has three.

For the Chinese, this was far from satisfactory. Early in their history they decided that the number of toes was a sign of rank. “In the era of the Zhou Dynasty it was resolved that the five-toed dragon symbolized the monarch, the four-toed dragon the aristocracy, and the three-toed dragon the ministers and highest public officials.”

However, the Japanese were of the opinion that all dragons originated in Japan. Toes were added as the dragons moved farther away from Japan, first in Korea and then in more distant China. The only reason the number of toes did not increase in – say, India – was that any more toes than five is not practical... Anyone who doesn’t believe this should try it out.

The images and quests come from the following sources in the following order:

http://www.onmarkproductions.com; http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons; http://en.wikipedia.org; http://www.ancientworlds.net; http://hu.wikipedia.org; http://hu.wikipedia.org