As a child I had the good luck to participate in the Japanese school system as well as the Hungarian one. I attended a real Japanese school for part of the first grade and from the 4th to 6th grades. I’d now like to summarize that experience and raise a few thoughts since reforming the Hungarian school system is currently under discussion.

First, let me briefly introduce you the Japanese school system. Kids in Japan attend primary school (shougakkou) from age 6 to 12, and then go on to 3 years of junior high school (chuugakkou) followed by 3 years of senior high school (koutougakkou). College or university comes after that. The Japanese believe that a person who graduates from a good university has excellent chances of getting a good job, which means being a success in life. So, naturally, every parent does their utmost to see that the children get the best possible preparation for college admission exams. The way to do that is to enroll the child in the best possible junior and senior high schools, which means that the schools with better reputations need to hold admission examinations, and that in turn means having the best level of preparation in the primary schools. There are already some primary schools that take only the most talented children. In addition to attending good schools, children take private classes and study ahead in schools called yukus, which they attend after regular school lets out in the afternoon, to obtain the extra information needed to do well in the exams. This system leads to the so called examination hell, in other words, to a childhood of immersion in studying with no time left to be a child. So let me make it clear in advance that I would not like to see this version of hell as the future of Hungarian education.

My own primary school experience was much more positive. And there were many things that stuck with me as highly positive experiences, and other things that taught me some major lessons. I’d like to describe them in ten points, which I’ve listed below:

- Cleaning up together

The first thing I’d like to mention is cleaning up together. After lunch every school day, the students cleaned up the entire school building - including the bathrooms. Japanese schools do not have cleaning staff. Each part of the school is assigned to a class for cleaning, and the classes form small groups for the detailed cleanup. Each week the responsibility for a given task shifts to a different group. One thing that it teaches children is not to dirty up the school since they are going to have to clean it up afterwards.

- Dividing other tasks among the students

Students have many other tasks in addition to cleanup. Each week a different group of children in each class is responsible for distributing the locally cooked lunch to the class, and afterwards for collecting the dishes and returning them to the kitchen. The children are also responsible for taking care of the class pet (which might be a frog or a turtle, or a goldfish, or a hamster or any other small animal), and for other tasks such as updating the bulletin board, etc. By the time they are completely at home in one task they rotate and need to learn the next one. My days as a Japanese student were exceedingly varied!

- The school’s garden and kitchen

A standard Japanese school has its own garden, where students grow their own fruit and vegetables. I was lucky in that my kindergarten also had a garden, so I already knew how to grow sweet potatoes at the age of 4. Growing these crops is only the first step. After the harvest, the children cook their own food from the produce. A good lesson for all schoolchildren is to see what work goes into raising a vegetable, which might make them more enthusiastic about eating them.

- Learning to swim in outdoor pools

Every school has its own (generally outdoor) swimming pool. It goes without saying that the children are responsible for maintaining these pools. They clean them, disinfect them, fill them and empty them. These pools are used in summer to teach children to swim. Although I was less than enthusiastic about the ice cold algae-filled water, in retrospect, I wouldn’t mind sharing it with our Hungarian children, who turn their noses up at our sparkling clean pools.

- Group projects

In the second half of primary school, every student got the chance to select a cause that he or she undertakes to support for the whole school year. The support means that all the children who picked the same cause (irrespectively of the class and even the year they are in) form a group to work on the project and everyone has to come up with something that would promote their cause. Just to give one example, in fifth grade I chose the environment and we were responsible for organising the collection of all the waste material in the school and for a roughly 1 kilometer (half a mile) area around it. It was a wonderfully positive experience and an opportunity to learn about the environment, not to even mention to good points for learning how to work in a group!

- Reorganizing classes every 2 years

During the six years of primary school, classes are reorganized three times. That means that students are regrouped every two years. One good point of this method is that every student gets to know everyone else in his or her year and students don’t get to be lazy in sticking with the same friends. Sometimes the transition is painful, but new friendships are quick to form. This “freshening up” of classes also helps to eliminate prejudices.

- Integrated education, helping students catch up

No matter where I went to school, there were always one or two kids in the class who came from disadvantaged homes, who needed special instruction or who had a disability of some sort. This was taken in stride in Japan. All students attended all classes together. The only difference was in the criteria used to grade our work. If a child had a very serious illness or disability, the school employed a separate educator to help him or her throughout the day. One very good outcome of the method was to eliminate many taboos and prejudices in me at a very young age and to give me the chance to learn about children with special needs and what those needs were, something I would never have had the chance to see close up in the Hungarian education system.

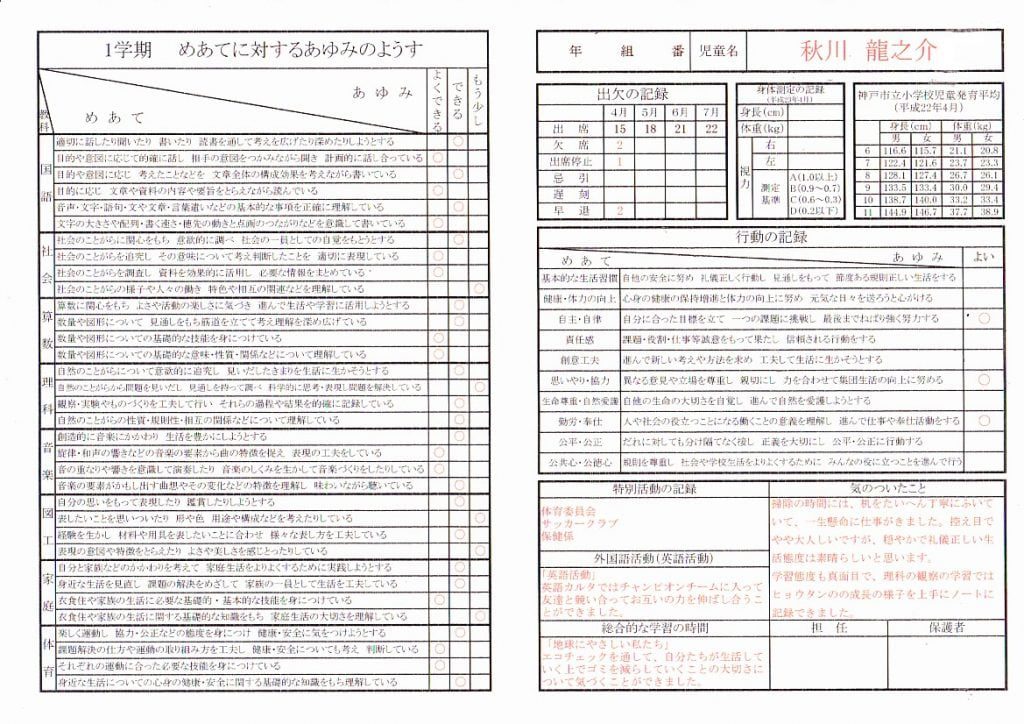

- Report cards

There are no grades in primary school report cards. Actually, the emphasis is not even on the subjects. The report card has three columns (quite satisfactory, satisfactory, needs a bit more work) that serve as guidelines on how well the child is developing and what needs to be targeted for future development. In addition, older students do not get a single “grade” in a subject, either. For instance, in mathematics they are graded according to the following criteria:

- Is the student interested in Maths and does she/he use the Maths learned in day to day life?

- Does the student solve the task using logical thinking?

- Has the student absorbed the necessary knowledge regarding quantities and shapes?

- Does the student understand the meaning of the words related to quantities and shapes, and has she/he learned their major features and the relationships between them?

Oh, and clearly, no one fails in primary school. I think that a grading system like this tends to be a far better internal motivator to learn than having students working merely for grades…

- Mentoring

Students in the final grades of primary school have the opportunity to mentor first graders. The mentors are assigned to a child – generally of the same gender – who they introduce to school life, to the building, to its rules, and with whom they organize joint programs. For the young children this serves as a bit of extra support during the initial uncertain period, while for the older ones it is a chance to be responsible for another child, and a way to learn how to teach and help other people.

- Clubs and student circles

Each student must choose a club or educational circle to belong to for a given school year. The meetings are in the afternoons. There is a wide variety of student circles available, including ones involving sports, musical instruments, cooking and just about everything in between. These circles serve as a way of forming cohesive groups while they do away with the need for private lessons, which in Hungary are very expensive, and they keep children busy with quality work through the afternoons.

I could list some other good points of Japanese schools in addition to the above ones. Still, I would be quite satisfied if schools in Hungary were to introduce these ten points and make them more livable and likeable.

Image sources:

www.oklab.ed.jp

weblog.city.hamamatsu-szo.ed.jp

edupedia.jp