Many years ago I had a discussion about Christianity with a Japanese colleague. That was when I learned that Christianity had reached Japan in the 16th century but did not really spread. (In today’s Japan with its population of 130 million, only about a million and a half people consider themselves followers of Christ, while the vast majority are either Shintoist or Buddhist.) Since I had never before heard of the persecution of Christians in Japan or of the Japanese Christians who were martyred for their beliefs, my colleague suggested I read a novel called “Silence” by a 20th century Catholic(!) Japanese author named Shūsaku Endō.

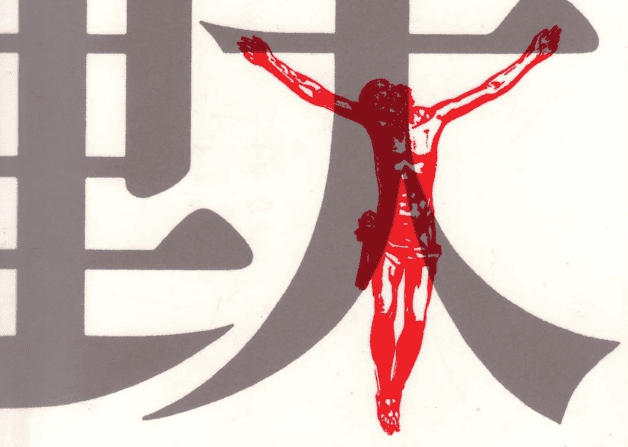

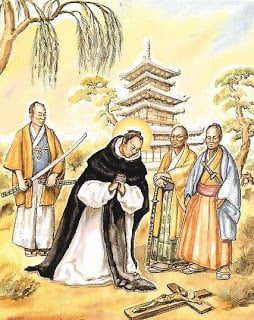

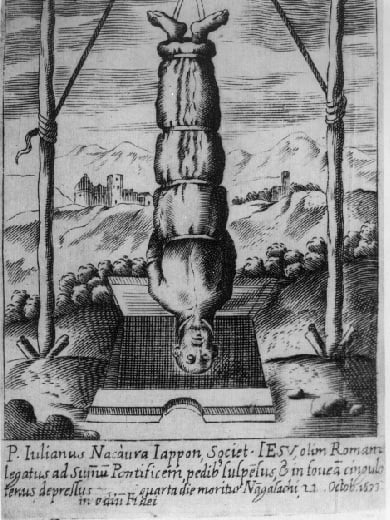

“Silence” is based on historical events and takes place in 17th century Japan, following the defeat of the Shimabara Rebellion and the execution of 35,000 Japanese Christians. The novel starts with the news that Father Ferreira, a defining representative of the Jesuit order, committed apostasy (denied his faith) amidst the merciless torture he endured. Two disciples of Ferreira arrive in Japan from Portugal on the news, to learn their mentor’s fate and to spread the Word. The novel is focused primarily on events as seen through the eyes and written in the letters of one of them, Father Rodrigues. We learn that the first Jesuit missionaries arrived in Japan in the 16th century, to the Gotō Islands and Kyūshū. Initially they were successful in converting the Japanese peasants and the daimyo-s (the great lords who were vassals of the Shogun). However, at the time Father Rodrigues arrives in Japan, the Christians are being persecuted and are suffering a variety of forms of torture. They are forced to stamp on holy pictures for a start, followed by crucifixion or being hung upside down above a pit and slowly bled out to force them to renounce their faith, or they are killed outright. The mission can only continue underground (Kakure Kirishitan-Hidden Christians). Throughout this, God is silent and the priest must finally decide whether to choose a martyr’s death or renounce his faith and continue to live. Is he more useful to his community dead or alive?

By the end of the 16th century, thanks to Portuguese Jesuits, and Spanish Dominicans and Franciscans, the number of Christians in Japan reached 300,000. The Shogun initially supported the Christian missionaries and encouraged them to build commercial ties with Europe, hoping to break the power of the Buddhist priests. However, the rivalry between the Catholics (Portugal and Spain) and the Protestants (England and Holland) quickly led the Japanese leaders to lose confidence in them as they began to see the Christian missionaries as a bridgehead to colonial military operation. It would not be without precedent. In the Philippine Islands, eventually named after Spain’s King Philip II, the first to arrive were the Spanish missionaries who converted the natives and then the area was declared a colony of Spain. To protect themselves from a similar hazard, which might descend upon them from four different directions, the Japanese passed their first anti-Christian laws. Then, building on them, they introduced increasingly brutal torture and executions in a bid to eliminate Christianity from Japanese soil entirely. The Christian clergy, who until then had been trying to spread the Gospel in Japan, likened this to having planted a sapling in a swamp, where it was unable to take root, and would wither.

The original religion of the Japanese people is Shintoism, a shamanism that believes in forces of nature, has 8 million gods, and believes man to be godly in origin. The other religion they follow is Buddhism, which proclaims the basic truths of life and responsibility for thoughts and deeds. An exclusive belief in the one Jesus Christ is not compatible to either. In the more than 2000-year-old Japanese culture, a Japanese Christian tends to stick out like a sore thumb. In the 1860s Japan appeared ready to open its doors to the world, but it only proclaimed complete freedom of religion after the Second World War. Novelist Shūsaku Endō (1923-1996) lived through a time when his Christianity separated him from his contemporaries. His ideal was to see all Japanese becoming Christians while remaining 100 percent Japanese. In the meantime, most people in Japan have minimal knowledge of Christianity. Most of those who know more have evolved their images of Christianity through Endō’s exceedingly popular books. Although they no longer persecute followers of Christ and there are Catholic schools (which qualify as elite), and Christian churches (where Christian style weddings are very popular even among non-religious people) and they have elected Catholic and Protestant prime ministers (seven, to be exact) there are no mass conversions in Japan. One missionary explained this by saying that the Japanese consider human relations and harmony to be more valuable than truth. If forced to choose, they will always make a sacrifice for their fellow men, he said.

Sources of the images in the order of appearance:

http://geektyrant.com

http://jamesmys.blogspot.hu

http://motoretta.exblog.jp

http://www.ourladyofgracemonastery.com