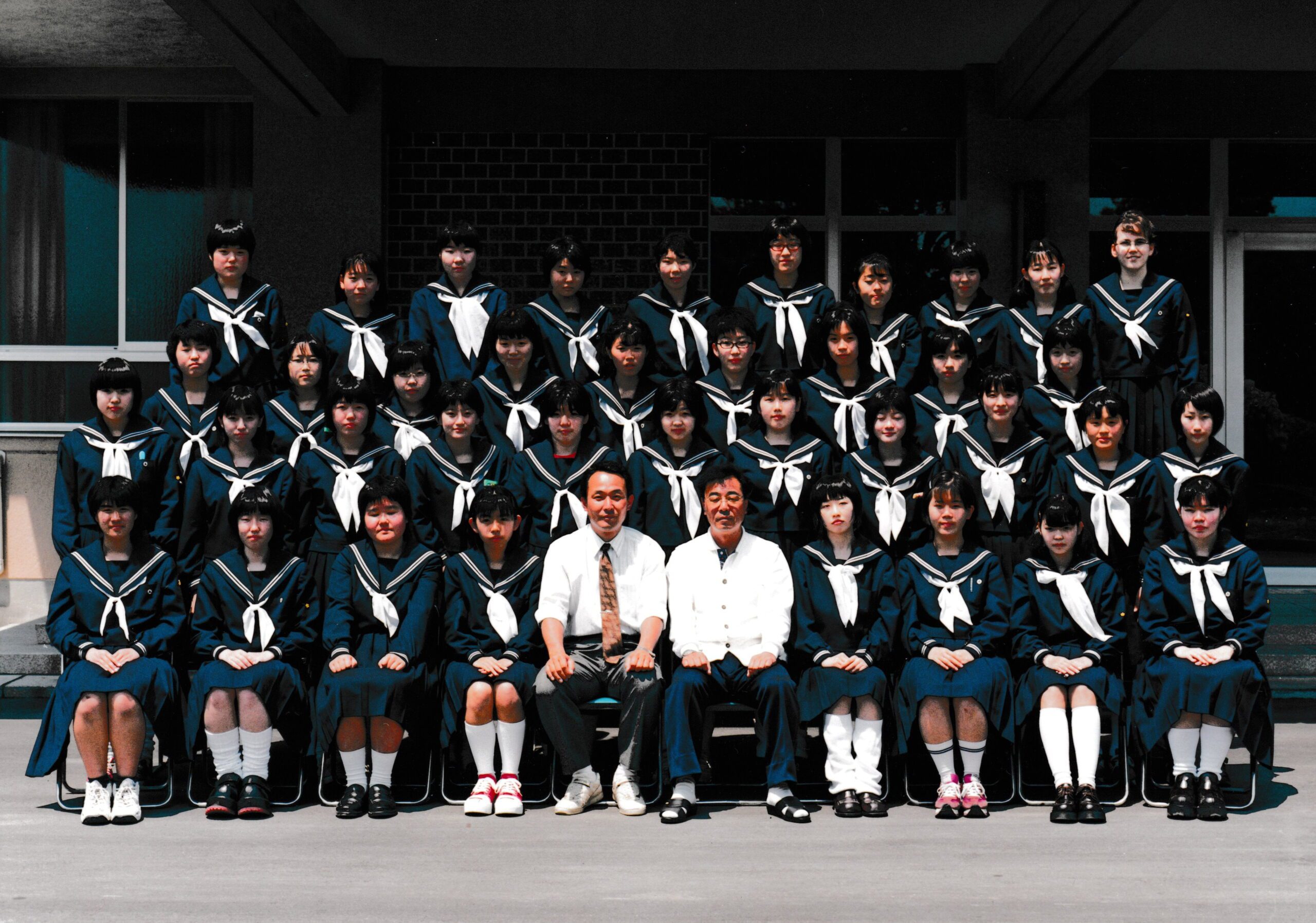

How do we behave, communicate, think, relate to work, care for our families, and manage our day-to-day living and conflict situations? Obviously, every individual is different but still, some features tend to be typical of a given culture. And we learn the vast majority of the attitudes that become our norms during our years at school, within the walls of the place where we study. I don’t think it makes much difference whether we come together with a Japanese exchange student, a business associate, or a colleague, because in all cases figuring out the meaning of the words and actions of the other party is a lot easier if we know something about the Japanese educational system that molds and shapes a young Japanese person. That’s why I thought I’d offer some nuggets from my memories as an exchange student at a Japanese secondary school. I figured that I’d focus on the aspects of the stay that had the deepest impact on me in the positive sense, and the ones that really shocked me. However, at the outset, let me underline that there is no way I can present the Japanese education system in all its detail. One reason is that I was always on one side only, that of a student.

I had heard a great deal about Japanese precision, miniaturization, and determination before traveling there. Still, as a secondary school student, the well-known rumor that most concerned me was that Japanese students were always studying, day and night alike. I guess everyone would be a bit worried regarding this “image,” especially on the eve of becoming a Japanese secondary school pupil as an exchange student. But were my fears well-founded, and how true is the belief?

In Europe the 8+4, 4+8, and 6+6 primary to secondary systems are the most widespread, but in Japan the system is 6+3+3. In other words, in Japan there are 6 years of primary school followed by 3 years of junior high school and another 3 years of high school. (In both Europe and Japan, the system is made up of 12 years of education between the ages of 6 and 18.). I was 17 years old, and had just finished my third year of high school when I transferred to Japan for a year. Based on my age and the number of years of school I had finished, I should have been in the final year, which in Japan meant the third year. So I was really upset and hurt when I was told that from September to March I’d have to attend the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of the FIRST high school year, and then, in April I’d be allowed to attend the second year for one trimester. Now, of course I understand the reason for that decision and I can only thank them for organizing my year in that way. (I’ll offer more details later on when describing the Juku system.)

While many things in Japan are considered eternal and unchangeable, many other things have changed a great deal in the past 25 years and that includes the educational system. (See the 3rd Japanese education reform introduced at about the turn of the century). While in the 1990s six days of school a week, uniforms, and a relationship between teachers and students based on highly authoritarian principles were still common, they are quite rare today.

In those days I found it comparatively easy to understand the essence of the Japanese group mentality. I learned the true meaning of the saying that “if a nail sticks out, you have to hammer it in” when I saw what happened on the 7th day of the week – the extremes and extroversion in dress and behavior. Someone getting to know Japan today would have a tougher time noticing this, since the sharp demarcation line is disappearing. What used to be a rigid system is becoming relaxed in many ways. In those days, 17 years ago, every one of my classmates wore the exact same clothes, the same socks, skirts, blouses, raincoats, gym suits and the same slippers six days of the week, and no one was allowed to use makeup or wear jewelry. The superior rank of the teacher compared to the student was demonstrated very clearly in communications, which were actually one-way only, so it became very clear that the seventh day of the week was the day when students could compensate for the strictness. I was shocked by the cosplay (play costumes i.e. performance art dress) costumes worn on Sundays, but knowing the many restrictions and requirements in force through the rest of the week, I more or less understood the phenomenon.

The idea of “sameness,” of uniformity, helped to disguise social differences within a school but for many rebellious and individualist types, for young people thirsty for creativity, this total ban on demonstrating any individuality and/or original thinking was just fanning the flames. Of course, everything is relative. One might call it “freedom” in an exceedingly regulated system when, in a given semester students are allowed to choose, for instance, which of five sports they would prefer. I tend to like rules and to think and function in terms of systems. I’m okay with restrictions and limitations, so I was one of these students who didn’t need to put on a cosplay costume to express myself. Instead, I was pleased to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the educational system. I was delighted with the club system offered by my public (government run) school, which gave students the chance to choose optional activities outside of the mandatory curriculum, and provided the technical conditions. All the schools in our town had their own athletics fields, indoor sports arenas, swimming pools, combat sport centers, tennis courts, music rooms with 40 upright pianos, orchestra rehearsal halls, home economics rooms with 40 sewing machines, model kitchens able to accommodate 40 students simultaneously, plus, of course, all the opportunities to learn traditional Japanese arts. For me, this felt like heaven on earth, not restriction.

I was not happy in that I wasn’t able to derive a second degree equation but had to choose between four possible multiple-choice answers. And I was furious that my level of English was assessed by handing me a photocopied page from a 40 page English tome that I had read back home. They had deleted 15 words from the page, and my job was to put them back in. To make it worse, writing in a synonym or another grammatically correct word that fit the context but was not the original word was awarded zero points. As a student raised in our Hungarian educational system, I found it hard to stomach their grading and evaluation system as well as the fact that, in Japan, school “communications” were unidirectional. Before I had the chance to wonder how it was possible to teach, for instance, a foreign language here, I got my answer in English communication class: the entire group read the texts aloud in unison. That was about the only time students could open their mouths in school. I cannot say that the system in which students were relegated to passively receiving information and allowed to display their knowledge only in written answers to multiple choice questions was conducive to fostering independent thinking and expression. At the same time, I soon realized that the Japanese obtained vast amounts of lexical information over their school years. It was only later that I realized how, and how shockingly efficiently, they put that knowledge to use. With sufficient or maybe even excessive self-confidence I believed that logic and the ability to think independently and express oneself were “the most valuable of all skills” and I had no doubt that my knowledge level was quite sufficient for Japan. I won’t say that I was absolutely off base, but my attitude did change significantly over time, partly because of a couple of smacks I had to endure. I was stunned to realize, for instance, that when taking math tests, although I understood all the theory and knew exactly how to apply it, I still was unable to do well. While my classmates had learned certain schematics by heart that allowed them to solve problems at lightning speed, I was left to rely on logic. And the system gave me neither the opportunity nor – especially – the time to use logic. The essence was that no one cared about my ability to prove Pythagoras’ Theorem at any time or to calculate the cosine of 30°. I was expected to be able to know how to grab the answers without thinking about how they came about and use them in working out the problem. I’ll admit that my classmates were much more experienced in this than I was. And as I discussed in an earlier blog (The bumpy road to understanding, 10/09/2015), we were graded in percentages, which determined our standing within our own groups. The overall group outcome then became a reference value that set the highest, lowest and average percentage value for the entire class. This is why it mattered what my performance looked like compared to the others and how quick I could be.

And this is where I go back to my original thought: studying day and night. You need time to memorize stuff. And since memorizing is what Japanese students tend to do most, it is understandable that a motivated student who wants to go on to college has about zero leisure time. Of course, to complete the picture, basic class time runs from 8:30 a.m. to 3:35 p.m. (That includes six 50-minute classes each day + a mandatory start to the day of 15 minutes of solving math problems in the classroom + lunch + 15 minutes of mandatory school cleanup after classes.) When that part of the day is over, most of the students attend some sort of club activity as often as six days a week. The clubs can last until 6 p.m. so the studying, the rote learning, the memorizing, comes afterwards. But let’s stop here for a moment.

The information flow in the schools goes from teacher to student only, but that doesn’t mean a student can understand the material without asking questions. They get to ask the questions elsewhere, in what they call “evening private school,” the juku (Crammer), which completes the picture. 8:30 a.m. to 3:35 p.m. is school, followed by clubs, followed by private school, followed by study at home. That is the real timeline of studying day and night, and it is quite literally true.

I would like to flesh out and deepen this description with another paper, one describing the Juku system, including the types of private schools, their objectives, and the nature of the work they do. Perhaps the two studies in combination will help give readers an accurate picture of the education system.

All photos are my own.